7 Surprising Facts About Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

For the entirety of fall 2023 I was enrolled in my first academic course on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. I have studied the sutras before, both on my own and through the lens of my Teacher Training and Advanced Teacher Training at the Sivananda Yoga Retreat in Bahamas. For those interested in studying Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, I caution against going one route or the other; it’s important to supplement a more traditional yogic study (as in the environment of an ashram or under the guidance of a practioner-guru) with academic study.

Studying the Scriptures: Traditional Gurukulam Method vs. Academic Scholarship

There are certain pros and cons to both academic and gurukulam study; one without the other can easily fall into the trappings of dogma. I was certainly alarmed by much of what I came to learn during the course of these last few months. While this new knowledge does not necessarily contradict my previous studies in a more traditional yogic environment, it does pose questions of relevance, adaptation, and context that are simply not available to a student in a gurukulam setting (no matter how modern).

A part of scriptural study under the guidance of a guru or spiritual preceptor is a surrender to his or her point of view; while you are most certainly welcome and even encouraged to ask questions, it’s assumed that your understanding is shallow and the guru’s opinion is the correct one.

In academia, there is more of a respect for a difference in opinions, but this comes at the expense of a sense of authority. The authority levied by the guru and implied by his/her stance allows for an exploration of depths that may never be traversed in an academic setting, where one can easily become swayed by the argumentative charisma of scholars trying to prove their point.

The guru is also a scholar; s/he has spent many decades (typically) studying the subject matter. There is a level of expertise here that should be respected, that deserves reverence and honor. Still, a guru is one person, with one point of view. The guru teaching on an Advaita Vedantin scripture, for example, will not take time to teach the Buddhist scriptures, unless (of course) he is teaching from Sankara’s commentaries and is mentioning the Buddhist scriptures out of context, to disprove them. The point of the gurukulam is not to present you with opinions (plural), but to take you deep into one opinion (singular). This is because too many point of views can rightfully cause confusion. The danger here is that somewhere along the way it’s easy to adapt someone else’s point of view as our own. When this happens we are more prone to ignore the things that seem out of sorts, especially because in a gurukulam setting, we are taught that we can’t trust our minds (and opinions). While this is true to an extent, there is a difference between the mind and intuition. In this case as with many others I have found that when things feel a little too neat, they most likely are.

In academia, scriptures are contextualized in time and place. The textual history and tradition of a source text is always relevant, especially when it comes to adapting ancient practices for modern times. In academia, multiple translations and commentaries are presented, with neither one being given more weight than the other (ideally). This an extremely fruitful environment for questioning. It’s also dangerous; it’s easy to run around in circles and end up chasing your own tail. If this happens, it’s important to realize that (1) things in practice and in theory are rarely the same and (2) multiple points of view (whether opposing or not) can be true at the same time.

In both settings, it is wise to remember that:

It is the mark of an intelligent (and wise) mind to be able to entertain ideas without accepting them.

The paths are many, the Truth is one.

Please also note: I use the word “fact” in the title of this blog post loosely. Ultimately, everything is up to perspective.

#1

There is no original Sanskrit text of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (yet).

Most of us know that Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras has many translations (into English and other languages); while we may question the veracity of a specific translation, we don’t think twice about the authority of the source text in Sanskrit. The reality, as it turns out, is that the written transmission of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are many, and it’s hard to tell which one is closest to the original oral transmission of Patanjali himself. These written transmissions can be radically different from each other and are typically colored by where they come from — the region and the person that recorded the words. There have been many misunderstandings in later commentaries due to, for example, translating from a Sanskrit manuscript in which the scribe, mishearing a word in one of the Sutras, recorded it incorrectly!

(FURTHER LISTENING) Interested in diving deeper? Listen to Episode 11. Philipp Maas | The Pātañjalayogaśāstra and its Textual History on Seth Powell’s Yogic Studies podcast here.

One of the key understandings that arises from academic study of the sutras is that the passage of knowledge cannot be amputated from the source transmitting it. This is personally the main con of the gurukulam method for me; within the gurukulam system, the guru’s word holds authority tantamount to it being the source. Those deeply vested in the gurukulam system will argue that a guru’s word is law, and I am not arguing that his/her word is not law. I am merely pointing out the necessity to ask: law for whom and to what end? In this same vein, the realization of the multiplicity of written and oral transmissions makes one realize that while having faith in the scriptures is important, it’s also important to ask, which version of the scripture? Because… the finger pointing to the moon is not the moon, after all!

#2

The Yoga Sutras were written for Brahminical renunciates.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras were intended for Brahminical renunciates—that is, male monks. And these were not just any male monks, but monks belonging to a certain section of Indian society—the Brahmins. This part of Indian society was already predisposed to spiritual practices and certain philosophies. Also, the Yoga Sutras were composed in Sanskrit—a language that was only available to the elite in Indian society (the Brahmins and Kshatriyas). The Yoga Sutras, however widely-read or ‘practiced’ they are today, were never intended to be read or adopted by the working or laboring masses. They were intended for those who, to a certain extent, had the luxury to meditate and practice yoga, a predisposition for the practice that was cultivated by education granted by virtue of status, and the circumstance of birth that made the pursuit of yoga socially acceptable.

(FURTHER READING) For more information about how casteism may manifest in yoga spaces, head over to Yoga International’s article written by Anjali Rao found here.

#3

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras were composed in a time when there were competing philosophies.

The Brahmins had their own philosophical worldview. The Yoga Sutras were intended for Brahmanical renunciates and as such, were composed with the purpose of supporting a philosophy that would feel familiar to Brahmins during that time.

#4

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras belong to the Samkhya school of philosophy.

Why is this (and point 2 and 3) relevant to note?

Consider that all human action and speech has a motive, even if that motive is vague, like the need for expression, or altruistic, like the desire to relieve suffering or make others’ lives better. Motives are usually multiple (we want to help someone because we want to help them but also because we want to feel of use and therefore, accepted and loved) and the more subtle a motive is, the more it is hidden from us. Motive colors not only the way action and speech is received but how it is given; the same goes for knowledge, which may be without motive (in theory)… until it is transmitted.

If you want to see this in action, consider a simple scenario: you need help for a task. How would the way you ask for help differ if you were to ask a parent, a close friend, a teacher or guru you idolize, a business associate, or a stranger? To go further, up the stakes—you need help for a task that you must complete within the next hour, otherwise the one you love the most will drop dead (unrealistic and extreme, I know, but let’s run with it). How would the urgency and stakes of the situation change your phrasing (and body language cues)?

I mention this latter example because when it comes to spiritual matters, what’s at stake is rarely negligible. Philosophy, when it is argued for, when it encompasses a world view, determines everything to the minutest detail—if you’re disproven, everything you believe in, everything you know to be true, everything you stand for, everything that gets you up in the morning, can crumble in seconds… and for many, this can feel like a matter of life or death! That’s why it’s important to keep in mind who the Sutras were written for (and by), when they were written, and why they were written. The Sutras were meant to convince a certain sect of society to prescribe to a Samkhya point of view. They were meant to be convincing—in modern-day parlance, the Sutras could be seen as a very knowledgeable marketing campaign for the product of Samkhya philosophy.

#5

The Yoga Sutras exist in the world of Samkhya philosophy, which is dualist in nature.

In most contexts of yogic instruction of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras today (such as a teacher training—and at least insofar as I have and those I know have experienced it), the importance of the Samkhya world view is minimized or overlooked. In my lineage, for example, the school of philosophy is Advaita Vedanta — non-dualistic. So while we are taught the Yoga Sutras, we are taught it from the point of view of Advaita Vedanta. This is interesting to consider because the Yoga Sutras were originally compiled in support of a dualistic school of thought! In fact, Kaivalya, the final stage of liberation and the goal of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras is, in view of its context, often translated to mean complete aloneness. Kaivalya is achieved when purusa (the soul) has been separated from prakriti (the material world). This is in stark contrast to the more non-dualistic perspective which most yoga schools and teachers espouse, where yoga itself is translated as a means of union (not separation).

#6

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras may be an amalgamation of concepts from various philosophies of the time; compiled, not composed.

Certain scholars suggest that the Yoga Sutras may have been a way of absorbing Buddhist and other concepts and reappropriating them for a Brahminical renunciate audience. This is relevant because certain terms (like dharma mega) can be easily misunderstood if they are not contextualized with the knowledge of where they came from (Buddhist thought, Buddhist scripture). As it turns out, many of these terms existed first in Buddhist scripture; scholars argue that these terms were so commonplace at the time [when Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras were composed (or compiled)], they didn’t need to be explained in context. This is relevant because what’s happened is that in the absence of context, later commentators (many of whom today’s instruction of the Yoga Sutras is based off of) took an entirely etymological approach, breaking down a concept’s meaning based on the word itself.

To illustrate the danger in this, take this example: I write a book on how to become a photo editor. The first thing I write is that to edit photos, “you need a computer” and preferably “Photoshop”. If you are living in today’s age, you would know that I am referring to the use of an electronic machine that we call a computer and a specific program that you can install on that computer called Photoshop. At some point in the future however, in a different society, computers and Photoshop may be no more. Imagine then if the people of this future society took the task of becoming a photo editor and tried to understand how to complete it with the use of a “computer” and “Photoshop”, defining both words by their etymology. The word computer dates back to 1613 and originally referred to “one who calculates”. The words photo and shop would suggest something very different from the program called Photoshop. Out of context, then, my instructions to use Photoshop on a computer to edit photos might now translate to making calculations (?) and going to a shop of photos (??) instead.

(FURTHER READING) If you’re interested in diving deeper on the topic of the use of Buddhist ideology and terms in the Yoga Sutras, read the academic paper “Some Problematic Yoga Sutras and their Buddhist Background” by Dominik Wujastyk here.

Finally, as far as I’m aware, even the question of who Patanjali was and if he did, indeed, compose the Yoga Sutras is up for debate. Many scholars suggest that the Yoga Sutras were actually a compilation, and that while some of the sutras were composed by Patanjali, others were passed on from other sources.

#7

There is no singular definition of what yoga is (really) and Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are not the only text of authority on yoga (actually).

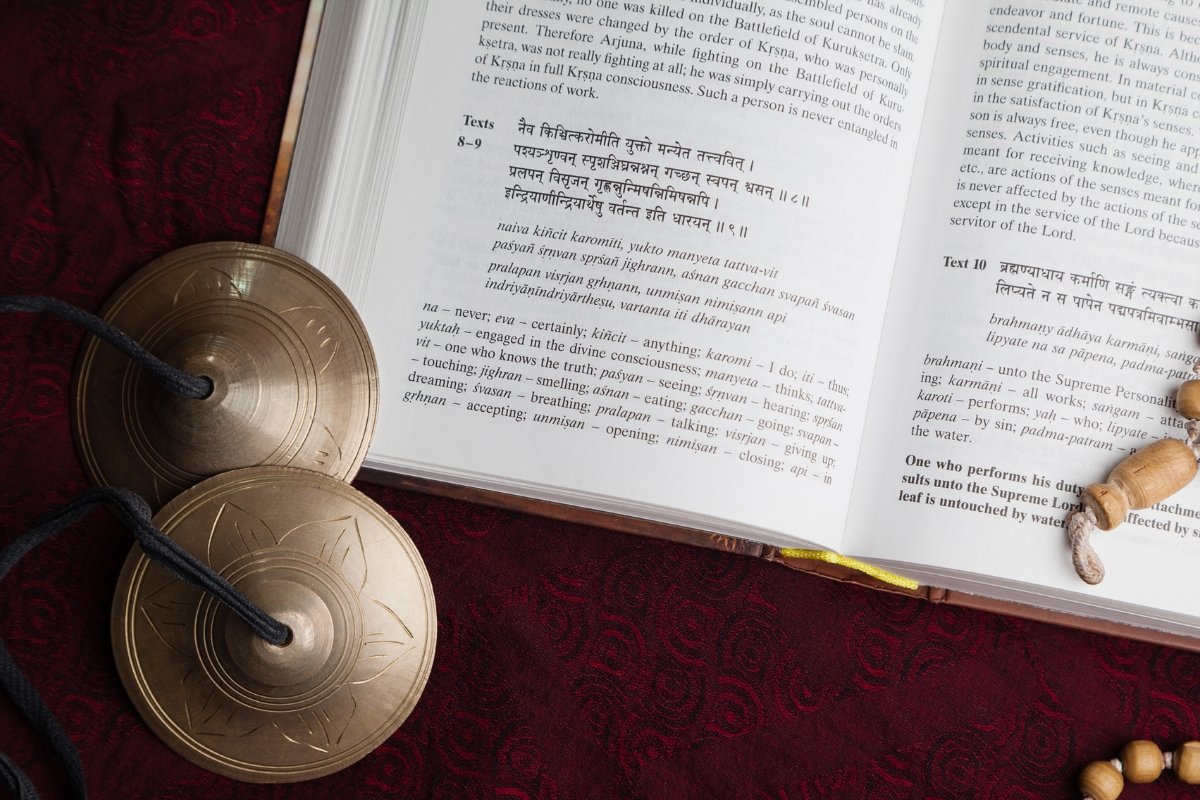

It wasn’t until Vivekanda’s address at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in 1893 that we began to equate Yoga with Raja Yoga and Raja Yoga with Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. The truth is that there are many other scriptures prescribing paths to yoga, such as the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, several tantric texts (that I am not yet familiar enough with to name off the top of my head), the Bhagavad Gita, and select Upanishads. What we practice today (and what we are taught in most yoga schools, even the more traditional ones!) is in fact more of a hodgepodge of all of these scriptures. This makes sense, because yoga as prescribed by Patanjali would be very hard to practice without interpretation and adaptation to our times.

So, next time someone asks, “Are you a Yogi?”, instead of jumping to conclusions, let’s ask “What’s your definition of Yoga?”

(FURTHER READING) To learn more about the role of asana (the focus in most yogic practice today), read the academic paper “Sthirasukham Āsanam: Posture and Performance in Classical Yoga and Beyond” by Philipp A. Maas here and the academic paper “The Proliferation of Āsana-s in Late-Mediaeval Yoga Texts" by Jason Birch here. For more information on the trajectory of Yoga as a philosophy and practice throughout the centuries, check out the book Tracing the Path of Yoga: The History and Philosophy of Indian Mind-Body Discipline by Stuart Ray Sarbacker here.

In summary: when it comes to Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras and any scripture, for that matter, study the academic point of view to gain perspective and study the guru’s point of view to gain faith (or vice-versa). Know when to surrender to another’s expertise and when to develop your own. Above all, remember that words, regardless of whether they’re Sanskrit or English words, spoken or written, are not the objects and concepts they’re describing. The minute you try to communicate knowledge or experience of any kind (whether it’s through words or other means), it becomes a shade of its source. That’s why it’s important to acquire the knowledge (through transmission) and apply it (by living it)! Finally, and as always: the finger pointing to the moon is not the moon!